For the first time in many Augusts, I was alone at the cottage on Georgian Bay. My teenaged son was away at camp; my husband and I were taking a sabbatical from one another. Three of my longtime friends would be flying up from New York during the second week: but until then it was just me and the dog, me in the twin bed pushed against the wall in the yellow bedroom off the deck, the dog at the foot of the other twin. It was a solitary confinement I both looked forward to and dreaded, a time-out that would take me closer to what Emily Dickinson rapturously called her “blue peninsula.” Or drown me in longing for lost days.

I began every morning with a bowl of Cheerios topped with wild blueberries. The blueberries—with their flared crowns packed close together with sprigs of unripened gray or green buds in their cardboard container--had come from a farm stand on County Road 6 in Perkinsfield. The wild berries cost two Canadian dollars more than their cultivated cousins in the same pistachio green pint container, and someone who was looking to save a few bucks might opt for the cultivated blueberries, which were larger and juicier and did not need to be picked over before you ate them for breakfast.

But appearances, as every philosopher since Plato has observed, can be deceiving, and sometimes, as Emily Dickinson knew for sure, less really is more. In fact, the humble, diminutive wild blueberry, which is part of the wild heath family and grows in low-lying bushes in northern climes from British Columbia to Oregon and California in the West and the Atlantic Provinces to Maine and West Virginia in the East, is far sweeter than its plumper high bush cousin. The low bush wild blueberries contain far more disease-fighting anti-oxidants than the high bush variety, and their indigo-colored skins are rich in reservatrol, the same magic ingredient found in red wine. Moreover, the mouth-watering tang of the tiny berries, some no bigger than the honey bees that pollinate them, is just about the most sensuous experience you can have, second perhaps only to the rapture of your first kiss.

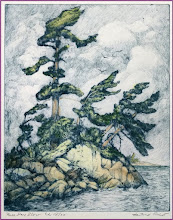

My first kiss took place on Addison Beach near the cottage on Georgian Bay on a July evening in 1966. Back in those days, we stayed on the island that my grandfather, William Kynoch, had purchased in the 1930s as a summer retreat for his wife and two daughters, the younger of whom was my mother. He had come upon the five-acre island, which included a small fishing cabin, on one of his walks from Balm Beach, where his wife, my grandmother, was studying landscape painting with Franz Johnston, a member of the Canadian Group of Seven. My grandfather fell instantly in love with the small island, which lay within wading distance of the mainland. With its stands of birch, white pine and oak, its wild blueberry bushes at the northern tip, its massive pink and white granite boulders that ringed its perimeter, it reminded him of the Scottish coast north of Edinburgh, from which he had emigrated years before.

On maps and surveys, the place was called “Tiny Island” after the township of Tiny in which it was located. Tiny was the name of one of the dogs of Lady Sarah Maitland, the wife of a Lieutenant Governor-General of Upper Canada, who ruled the region in the early 19th century when Canada belonged to Great Britain; the neighbouring townships were called Flos and Tay, after Lady Sarah’s two other lapdogs, a funny, stranger-than-fiction fact which my mother repeated to me year after year with undiminished merriment.

My grandmother, who painted the cabin’s kitchen cupboards with soaring gulls and wind-beaten pines, called it “Le Nid de la Mouette,” or “The Nest of the Seagull.” But everybody else--my mother, father, sister, aunt and two cousins, all of whom might be in residence in the sleeping cabin and boat house my grandfather built to accommodate his growing family--called it “The Island,” as if only the most unaffected moniker could sum up its singular magic.

Summer days on Addison Beach tended to all run together, singled out only by the vagaries of weather—the hot, still afternoons where there wasn’t enough wind to sail out to Seagull Island, the rainy mornings when you drove into Midland to shop or sightsee, touring Martyrs’ Shrine, the Gothic cathedral honouring the Jesuit priests who came in the early 1600s to convert the Huron Indians to Christianity only to be massacred by the Iroquois.

On that very hot July Saturday in 1966, so hot that you couldn’t walk across the beach without flip-flops, my grandfather, then in his early eighties, spent his morning sunning himself on the rocks at the end of the island, then, after a light lunch, took his usual walk down the beach to the two-bedroom cottage in the woods, which he had purchased as a retreat to work on the novel he had begun in retirement. The story goes that he was feeling a little tired and so decided to lie down and take a nap on the cot in the spare bedroom.

There was a bonfire on the beach that night—the family who was hosting it had been waiting all week for a windless day—and the kids in the cottages were sparking with anticipation. Not only did this mean we’d feast on roasted marshmallows and whoop around the fire like wild Iroquois, we’d also get a much later bedtime, because the bonfire never got underway until after dark, which in Ontario in July, meant well after nine o’clock.

It wasn’t until dinnertime that the family began to wonder what had become of my grandfather, and someone—my father, I think—was sent down the beach to find him, and discovered him stretched out on the cot, not asleep but dead. When my dad returned with the news, there issued forth a terrible keening from the women in the family that reached my sister and me sunbathing in the dunes on the mainland.

We hurried back to the island, forgoing our usual late afternoon swim, and were greeted with more sobbing. My dad was seeing to all the details that my grandmother, mother and aunt were too grief-stricken to undertake--calling the funeral home and arranging for a service and burial in the St. James-on-the-Lines church in the nearby village of Penetanguishene.

There was no family dinner at the long knotty pine table that night; we made do with leftovers from the fridge, and then because the crying showed no signs of letting up, and because we didn’t know what else to do and because no one told us we couldn’t, we slipped away to the bonfire.

The news that our grandfather had passed had preceded us. The parents at the bonfire hugged us, said what a gentle man, what a kind man, Will Kynoch was, and how much he would be missed. One or two reported that they themselves had seen him that very afternoon, making his way barefoot down the beach, his walking shoes in his hands, hardly, they said shaking their heads, the picture of a man in his last hours.

It’s possible that Bobby—and I confess that isn’t his real name--felt sorry for me, and that that was why he offered to walk me home when the bonfire died down to a few glowing coals. It’s possible that when I stopped to catch my breath from crying, I was acting with a certain calculation, hoping he would drape his long, skinny arm around me, hoping we would stop in the cool, maganese-dark sand a few hundred feet from where the water lapped against the island rocks. I had had a crush on this tow-headed, gangly-limbed boy for two summers. He had never kissed me. No one had ever kissed me. I didn’t even know what it felt like, having only read about it in books. But if something was going to happen, it had to be now, long past our bedtimes, when we were about to say goodbye and my dead grandfather was spinning above us among the Pleiades.

I never saw Bobby again after that summer. His family never came back to Addison beach, or if they did, it was for the first weeks in August instead of the last weeks in July. My parents built a cottage on the mainland, directly across from the island, the last project they created before they divorced. The island was sold in 1988 when my aunt could no longer afford its upkeep. My mother and aunt died within a year of one another, and now lie beside my grandfather in the St.-James-on-the-Lines cemetery overlooking Penetanguishene harbor. His pink granite tombstone is from Tiny Island. Its inscription reads: "Nescit Amor Fines" (Love knows no Bounds).

My morning cup of medicinal blueberries, eaten on the deck with the dog at my feet looking south toward Tiny island which is now a peninsula, will not bring back the name of the twelve-year-old boy who first kissed me, but I will never forget his sandy hands stroking and framing my wet face, the brush of our sunburned lips, his tongue pressing against mine like a mouthful of sweet, wild blueberries.

All posts copyright© 2010. All rights reserved. No part of this blog may be reproduced or distributed without attribution and/or permission of the author

Introducing Frida von Zweig

3 years ago